By Andy Smith

Ask today’s business students what they would do if confronted with an ethical dilemma in the workplace and most will probably answer with four simple words:

“Do the right thing.”

But what happens when the information you have to make a decision is limited or ambiguous? Or worse, it involves mutually exclusive choices? That’s territory Denny Gioia loves to explore in his MBA and Executive MBA classes at the Penn State Smeal College of Business.

“Ethical decisions and business decisions can be very different things,” says Gioia, the Robert & Judith Auritt Klein Professor of Management at Penn State Smeal. “When you combine the two, you have a complicated dilemma on your hands.”

Gioia arrived at Penn State more than 40 years ago, fresh out of Florida State University with a doctorate in Management. He also earned an engineering degree and his MBA at FSU.

“I loved teaching, but I was a classic introvert who didn’t know how to relate to a classroom full of students,” he says. “Over time, I learned the value of personal stories as a teaching tool.”

Some of those stories came from his time working for Boeing Aerospace during the Apollo lunar program in the late 1960s and at Ford Motor Company in the 1970s.

It was his job at Ford, however, that would most influence how Gioia thought about and taught about how organizations work.

“Before I took that job at Ford, I was a longhaired, 25-year-old idealist who marched for civil rights and against the attitude of big business at the time,” Gioia says. “I wanted to make the world a better place, so I went to Ford with the intention of changing the way they did things.”

It didn’t work out that way.

The Big Reveal

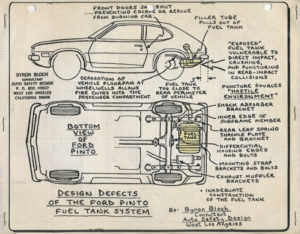

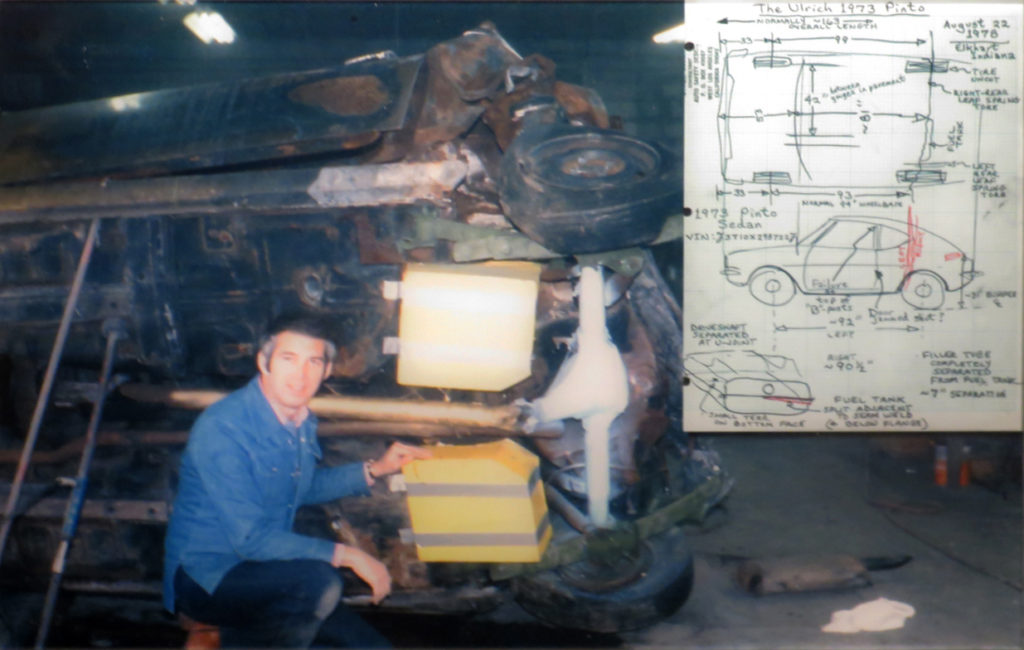

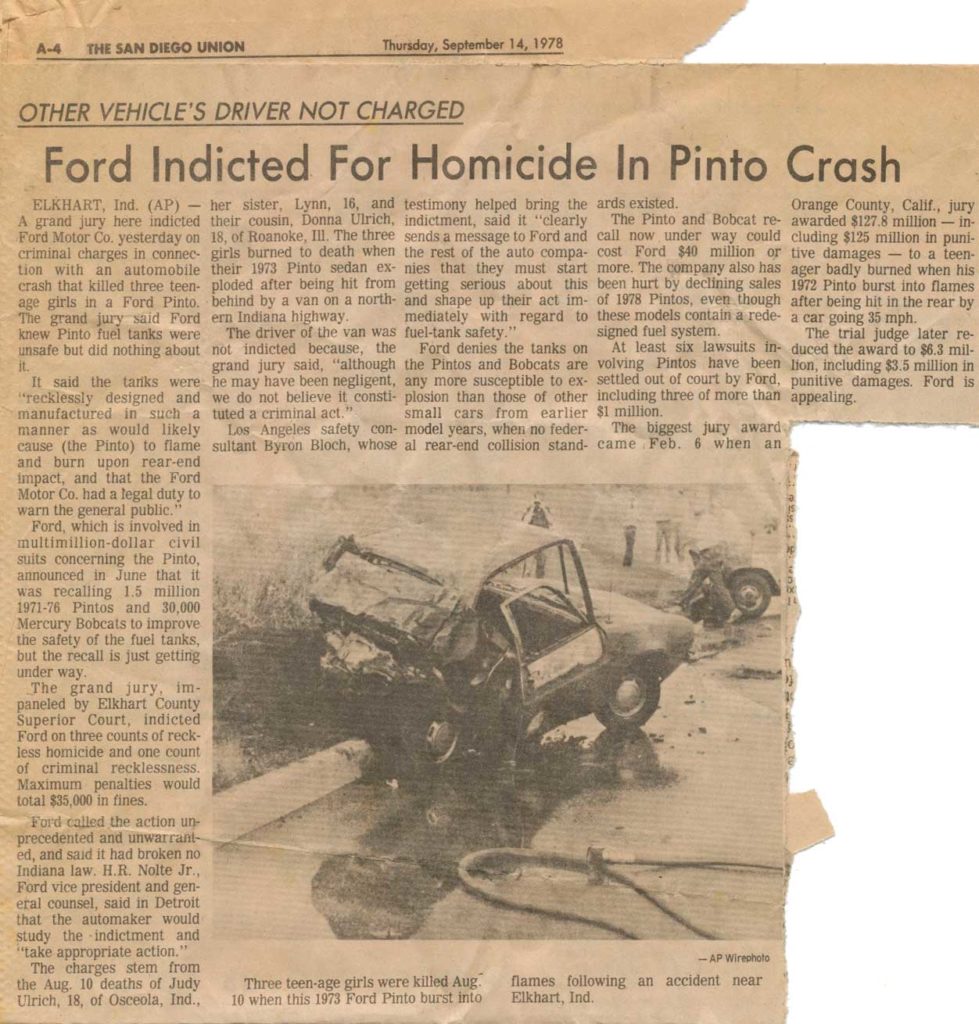

One of Gioia’s most impactful classroom stories involves the controversy surrounding the Ford Pinto, an infamous compact car that caught fire when struck from behind at residential speeds. Despite a flawed design, Ford chose not to recall the Pinto at the time.

“The Pinto case set the template for all following recalls,” Gioia says. “It’s a historically significant case, because it was the first time where a corporation, not the individual decisionmakers or executives, but the corporation itself, was charged with a crime — and the crime wasn’t negligence; it was murder. You can’t find a bigger precedent.”

When dissecting the Pinto case in class, Gioia answers questions students come up with if they could ask Ford’s recall coordinator. He then asks the students to put themselves in the recall coordinator’s position. After what is usually a spirited discussion, Gioia puts it to a vote: recall or no recall?

“Almost all the students vote to recall,” he says. “It’s then that I come clean and tell them that I was actually the recall coordinator and that I voted twice not to recall the Pinto. The room goes deathly silent at that point and the students get squirmy. They know they just voted to recall the car and they know I did not. The question then becomes: Why not? To them, it’s so obvious that I should have voted to recall…. So, what the hell just happened here?”

What happened is that a seemingly straightforward ethical decision collided with a more complicated business decision. It turns out that crash tests showed the Pinto was indeed dangerous, “lighting up” at only 25 mph because of its flawed design. Yet competitor cars without the same flaw would rupture their fuel tanks at an average of only 27.5 mph. Was it worth it for Ford to spend $30 million on a recall for only 2.5 mph?

Gioia says decisions to recall needed to meet two criteria: there had to be a “traceable cause” (e.g., identifying some component that broke), plus a pattern of problems. In an interview for a 2015 story in The New Yorker, Gioia had this to say:

“You have to be able to identify something that’s breaking. Otherwise, I’ve got an imaginary event. I try not to engage in magical thinking. I’ve also got to have a pattern of failures. Idiosyncrasies won’t do. Question is, do you have enough here indicating that these failures are not just one-off events?”

Gioia had neither; thus his dilemma.

Culture Matters

By the time he’s done with the Pinto case, Gioia describes his students as “discombobulated.” Little that they have been taught so far gives them guidance to deal with what happened at Ford.

To help right their worlds, Gioia shares lessons learned from the case, one of the most important of which is that culture matters.

“Organizational culture is both subtle and potent, and it will influence you,” he tells the students. “You can’t appreciate this until you are actually inside an organization to see how it affects you. I joined Ford with intent — to change it from the inside out. But after two years of seeing things from Ford’s point of view, I got flipped. If it could happen to me, it could happen to anybody.”

“By the time we’re done with this case, it puts the students in the position of being an organizational decision-maker and having to make a consequential decision,” Gioia continues. “After hearing about all the factors involved, most people conclude that they would have made the same decisions I did. ‘Doing the right thing’ is not easy because deciding the right thing to do is seldom easy.”

A Story That Still Resonates

Gioia left Ford in 1975, several years before Mother Jones magazine broke the Pinto story to the country. A 60 Minutes exposé followed, and in 1980 the case went to trial, which Ford ultimately won. Gioia “got lucky” and was never called to testify.

For nearly a decade after he joined Smeal, Gioia didn’t talk about his role in the Pinto case — “Eight years of not saying anything to anyone,” he says. In 1987, he realized the power the story might hold in class, so he wrote a teaching case about the Pinto. He got a lot of pushback from students at first. Some accused him of being “good at making excuses” for his actions at Ford.

“Maybe it has something to do with my grey beard, but I don’t get the same kind of response these days…most tell me they understand why I made the decisions I made back then,” he says. “I think modern students accept a wider diversity of views.”

Gioia does joke that it’s harder to surprise today’s students with the fact that he was Ford’s recall coordinator because “they Google everything.” But all these years later, he’s still teaching the case because it still resonates.

“Modern business students believe they are more ethical than previous generations, more inclined to do the right thing,” he says. “But deciding the ‘right thing’ to do is the really hard part. Using simple conceptualizations of ethical decision-making might work for some situations, but organizational life is too complicated for that.”

According to Gioia, we live in a VUCA world today — Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, and Ambiguous. To deal with that constellation of factors, instructors can’t be teaching simple conceptualizations of the right thing to do.

“Every important decision involves dilemmas and trade-offs,” he says. “If we want to teach students to be ready for VUCA contexts, we need to acknowledge that fact. Teaching with complicated personal stories and cases enables us to do that.”

Today, 45 years removed from the case he can’t shake, Gioia looks back and wonders: What would 2021 Denny Gioia tell a young 1970s Denny Gioia? Would he vote differently if he could go back in time?

“The honest answer…I just don’t know.”

Visual material in this article provided by Bloch Auto Safety Archives, autosafetyexpert.com

The Halo Effect: Why It’s So Difficult To Understand The Past | npr