Smeal researchers tackle the promises and challenges of transportation innovations.

Any Penn Stater who has ever been stuck in a long line of cars, vans, and pickup trucks crawling toward Beaver Stadium on Saturdays in the fall recognizes the need for safe, convenient, and efficient transportation.

But the future of transportation includes more than just making a noon kick-off.

New technologies are opening up the possibility of creating transportation that is not only safe and convenient, but also leads to a better environment and a thriving economy. These innovations, such as artificial intelligence-powered ride hailing systems and ride-sharing platforms, however, must be developed and deployed in smart, thoughtful ways, or they risk causing more problems than they can solve.

Penn State Smeal College of Business researchers are in the fast lane helping policymakers steer tomorrow’s transportation toward an ethical, economical, and sustainable future. The scientists are investigating ride-sharing platforms, such as Uber and Lyft, as well as autonomous driving systems that rely on cutting-edge technologies, including online platforms, artificial intelligence, and autonomous navigation. These technologies have emerged as promising options to address transportation challenges, such as traffic and pollution reduction, all while improving access to mobility and enhancing convenience.

Recent research has unveiled a nuanced scenario where the effects of ride-hailing on cities can be both positive and negative. Rather than alleviating congestion, these technologies seem to exacerbate it. Instead of mitigating pollution, they might even contribute to its escalation. The mission of the college’s researchers is to discover methods through which these technologies can foster communities that strike a harmonious balance between the potential of inventive urban mobility solutions and the imperative of economic and environmental sustainability.

Hail to the Future

It’s happening now. Self-driving vehicles are gliding along the streets of major American cities and picking up rides, like a scene out of decades of science fiction fantasies. It also inspires hopes for safer, greener, and more efficient transportation. However, the impact of these autonomous vehicles, or AVs — and ride-hailing technologies that will allow customers to conveniently arrange AV rides — remains complicated, says Sergey Naumov, assistant professor of supply chain management.

In a study, Naumov and his coauthor, David Keith, a senior lecturer in system dynamics at the MIT Sloan School of Management, found that better managing pooled rides — where fares are shared by multiple passengers traveling at the same time — on AVs could be the key to more efficient travel that can make a greener impact.

Because most people like to ride alone, if fares are not adjusted and managed to create distinction between individual and pooled rides, people will choose more individual rides — leading to more traffic on roads, including empty AVs en route to new passengers, Naumov says. Often called “dead-heading,” these empty rides cause more congestion and more pollution. However, according to the researchers, urban planners could leverage consumer preference to make pooled rides more palatable.

The goal is to create a win-win situation where ride-hailing operators, urban planners, and riders can work together for a more streamlined AV ride-hailing.

“One of the practical implications is just making sure that the strategies are aligned with multiple constituents,” says Naumov. “We were trying to show that it’s not orthogonal. The interests of ride- hailing operators do not conflict with the interests of urban planners.”

For example, one model that is currently in use in several states for conventional vehicles could possibly work for AVs as well. Managed lanes that use dynamic pricing to shape consumer choices on convenience could work to balance pooled rides and personal rides, adds Naumov.

“There has to be — and there will be — market segmentation, and it’s also important to think about the future of urban mobility from that perspective as well,” he says. “The idea is that you want to maintain differentiation, because unless you make pooled rides more attractive than personal ones, realizing the anticipated benefits of AVs will be challenging.”

Ultimately, the vision is a policy that allows ride-hailed AVs, public transportation, and personal vehicles to operate in harmony.

“We were trying to show that it’s not orthogonal. The interests of ride-

hailing operators do not conflict with the interests of urban planners.”

Ride-Sharing Platforms

Grappling with online and mobile ride-sharing platforms, such as Uber and Lyft, is not a future problem, it’s a current problem for many policymakers and urban planners, according to Suvrat Dhanorkar, Michael and Laura Rothkopf Early Career Professor and associate professor of supply chain management. Dhanorkar, who worked with Gordon Burtch, Kelli Questrom Associate Professor in Management at Boston University, also examined the complex interactions between ride-hailing platforms and traffic volumes.

Using monthly micro data from more than 9,000 vehicle detector station units deployed across California, the researchers found, for example, that ride-hailing had some evidence of reducing traffic on weekdays. On weekends, however, ride-hailing contributes to increased congestion. While dead-heading and increased convenience could be responsible for the congestion, this study also found that pooling options such as Uber Pool could help alleviate the situation.

Dhanorkar suggests that finding thoughtful ways to mitigate the problems of ride-hailing platforms is important for the future of transportation.

“There may be an impulse to hammer these companies by saying that Uber and Lyft, or any of the other ride-hailing platforms, are just causing congestion and are a nuisance, but there is evidence of the benefits to having these kinds of platforms,” said Dhanorkar. “For instance, it’s been shown that these platforms reduce drunk driving, so it’s good for society, in general, to have fewer drunk people driving around in their vehicles. Perhaps they do cause congestion, which we find. But we also want to better understand which areas are affected by this congestion and which circumstances are causing more congestion, so that we can provide policymakers with options to manage that.”

Dhanorkar cites congestion fees as one option. For example, New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority assesses congestion on any trip that starts, ends, or travels through Manhattan south of 96th St., according to the Uber blog.

“However, rather than having a blanket congestion fee, our research suggests that you may want to stagger that fee with different amounts or impose the fee on certain days of the week,” says Dhanorkar. “Perhaps there are also ways to better integrate some of these (ride-hailing) apps in the future with public transportation so that they complement each other.”

The study employs regression-based difference-in-differences analysis and various robustness tests to support these findings.

Whether it is delving into the data behind future transportation technologies, offering policymakers expert guidance, or helping consumers anticipate the next transportation trends, Penn State Smeal researchers are among the world’s leaders in finding ways to help travelers of tomorrow arrive safely, with minimal damage to the environment — and maybe even a little early to the tailgate.

“There may be an impulse to hammer these companies by saying that Uber and Lyft, or any of the other ride-hailing platforms, are just causing congestion and are a nuisance, but there is evidence of the benefits to having these kinds of platforms.”

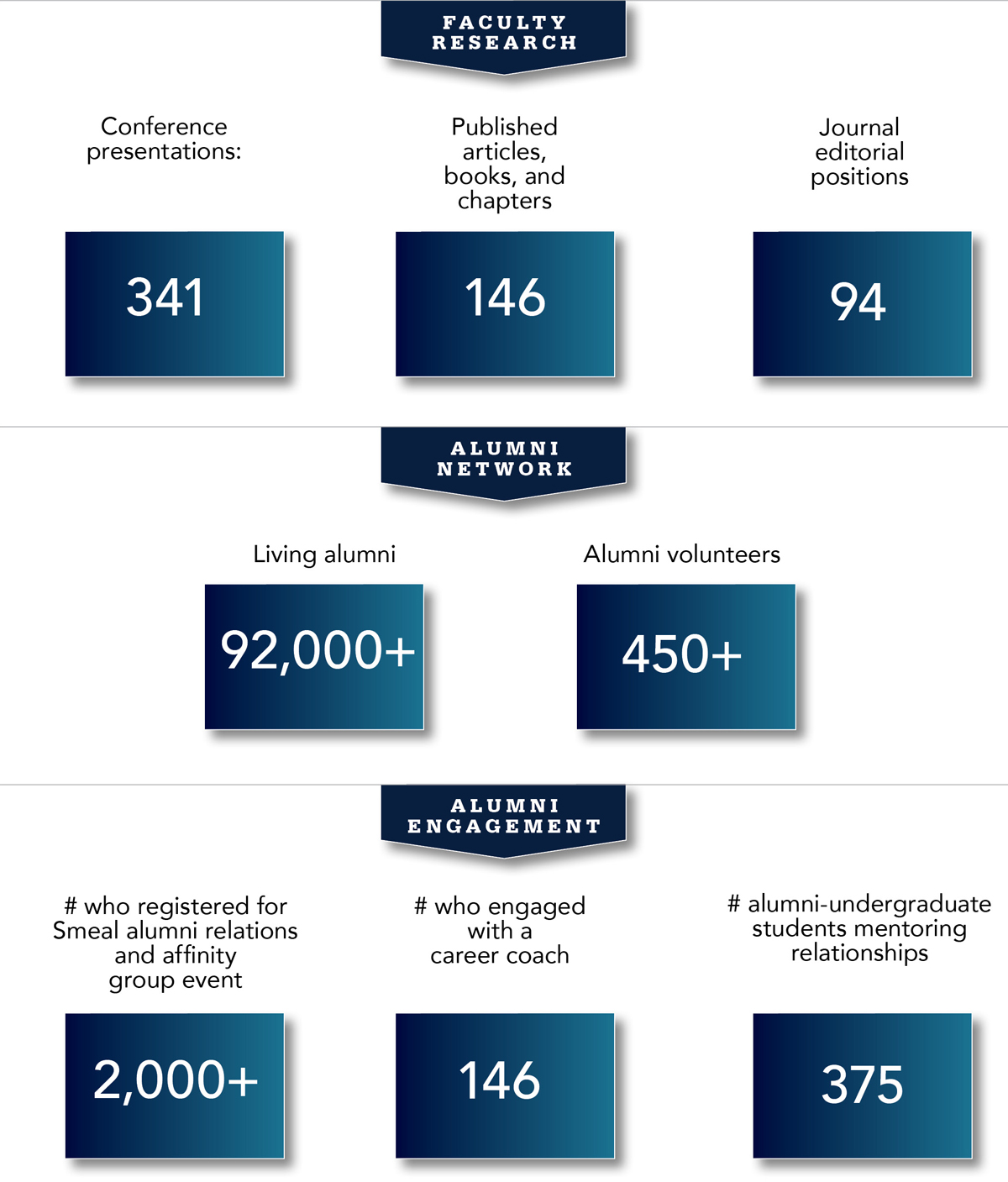

SMEAL BY THE NUMBERS